'Take advantage of your youth before your old age'. This statement of the Messenger, peace and blessings be upon him, was not lost upon the Muslims of the past. Taking advantage of time and youth can be done in several ways. One of these ways is embedded in the culture of teaching and learning that permeates throughout the Islamic world. The contributions of scholars of the past in the Islamic world across the various religious and secular sciences are far too many to be enumerated. Such contributions and advances were only made possible by the underlying social infrastructure, intellectual meritocracy and collective social concern. A striking feature of this culture of learning was that it enabled scholars to make significant and lasting contributions at young and tender ages. Across the ages, continents and sciences, Muslims, even teenage Muslims, contributed to the scholarly fabric that has been passed down to us from generation to generation. This present article seeks to highlight a few such examples of Muslim intellectuals making significant and lasting contributions in their youth.

Morphological Maturity

The 14th century bore witness to a number of great scholars and thinkers including Sa'ad al-Din Masud ibn Umar al-Taftazani (712 AH/1322 CE - 791 AH/1390 CE). Born in 1322, the Persian polymath al-Taftazani is perhaps one of the most celebrated scholars and intellectuals of the post-classical period. His works across the fields of linguistics, theology, logic and the principles of jurisprudence came to serve as textbooks in seminaries across the Muslim world. Even today, a number of his scholarly contributions serve as guides for advanced level students in seminaries across the Muslim world from Al-Azhar in Egypt, to Deoband in India and Konya in Turkey.

His ability and genius shone through even at a very young age. At the mere age of 16, Taftazani had authored a commentary on Tasrif al-Izzi', an elementary work in Arabic morphology. Producing a commentary on a staple text of study at such a young age is a feat in and of itself. However, this contribution in the form of a commentary was so elusive, comprehensive and full of insight that to this day, some 650 years later, it still serves as an indispensable handbook for anyone serious in their study of Arabic morphology.

Poetic Beginnings

The lands of 16th century Algeria cultivated a sharp-minded young thinker with a knack for poetry in the form of ʻAbd al-Rahman ibn Muhammad al-Akhdari (918 AH/1512 CE - 983 AH/1575 CE). It is reported that Imam al-Akhdari began composing didactic poems (nazm) from the age of 17. Didactic poems, the medieval equivalent to a set of flashcards, serve to organise knowledge in rhythmic verses so that it can easily be committed to memory and recalled seamlessly. By the age of 20, Imam al-Akhdari had penned didactic poems in astronomy and on the astrolabe. At 21, Imam al-Akhdari authored the poem he is most renowned for. His didactic poem, al-Sullam al-Munawraq, versified Athir al-Din al-Abhari's (d. 660 AH/1265 CE) manual in logic, Isagoge, in 144 verses. Five centuries later, this poem still serves as required study for students of logic.

Like Teacher Like Student

The Egyptian scholar, Jalal al-Din Muhammad ibn Shihab al-Din al-Mahalli (791 AH/1389 CE - 864 AH/1460 CE), was one of the great scholars of Shafi Fiqh during the 15th century. Imam al-Mahalli set out with the intention to author a commentary (Tafseer) on the Qur'an. Fate had determined that he would reach his demise before he could complete this endeavour. A budding student of his, Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti (849 AH/1445 CE - 911 AH/1505 CE) rose to the occasion and took on the task of completing the work started by his teacher.

Imam al-Suyuti mentions that he began this endeavour on the 1st of Ramadan 870 AH (1466 CE) and completed the Tafseer of the remaining half of the Qur'an in 40 days on the 10th of Shawwal 870 AH. At the age of 21, and within the space of just 40 days, Imam al-Suyuti was able to complete the Tafseer work started by his teacher. The combined commentary of Imam al-Mahalli and Imam al-Suyuti became known as 'Tafseer al-Jalalayan' meaning 'The Commentary of the Two Jalal's': the teacher, Jalal al-Din al-Mahalli and the student, Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti. Today, over 570 years later, this masterful work of Tafseer is still renowned as a key text due to its concise style and comprehensive nature. One cannot be considered a scholar until he has completed a study of this text. In seminaries across the globe, this work is still taught today and remains as one of the key works for students and scholars of Tafseer alike.

Hidden Talent

The 15th-century Algerian scholar Imam Muhammad ibn Yusuf al-Sanusi (832 AH/1428 CE - 895 AH/1490 CE) is well known for his pedagogical writings in theology. He writes for the student at every level, from beginner all the way through to the advanced scholar. His works are a mainstay in the study of theology.

One of his students, al-Mullalli, reports that the first work Imam al-Sanusi compiled was a commentary on al-Fara'id al-Hawfi, an inheritance manual in Maliki Fiqh. al-Mullali further adds that Imam al-Sanusi completed this work when he was approximately 18 or 19 years old. Imam al-Sanusi decided to show this work to his teacher who was so amazed and taken aback by the fertile mind and blessed pen of his student that he advised him to hide the work and delay its publication and circulation. His teacher feared that other scholars would become jealous of his ability at such a young age and Imam al-Sanusi would be afflicted with the evil eye.

Abridging the Ancients and the Moderns

One of the most important thinkers of the medieval period was the Arab historian 'Abd ar-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn Khaldun (732 AH/1332 CE - 808 AH/1406 CE). Born in Tunis to a family of bureaucrats, Ibn Khaldun's training and schooling prepared him to lay the intellectual foundations for the modern fields of sociology, economics and historiography. Ibn Khaldun saw history, the development of civilisations and society as a result of a series of causal processes dictated by laws in the same way the natural world is dictated by laws.

Such philosophical thinking and ideation was a direct result of his studies during his early life. Some 150 years prior to Ibn Khaldun, the 12th-century philosopher-theologian, Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (d. 606 AH/1210 CE) produced a work called al-Muhassal al-Afkaar al-Mutaqaddimin wa al-Muta'akhkhireen. This phenomenal work, al-Muhassal, sought to integrate the Hellenistic and Avicennan philosophical traditions into the wider theological Kalaam tradition as a single unified system of thought. Imam Razi endeavoured to organise the positions and arguments of ancient Greek philosophers and contemporary Islamic philosophers and theologians under the thought structure of theology.

The work, al-Muhassal, stands as a landmark contribution in philosophical theology in attempting to capture and preserve the breadth and depth of philosophical and theological thought across the Islamic world and beyond. al-Muhassal is an advanced synthesis of philosophy and theology which demands an exceedingly sharp mind and a familiarity with multiple distinct intellectual traditions.

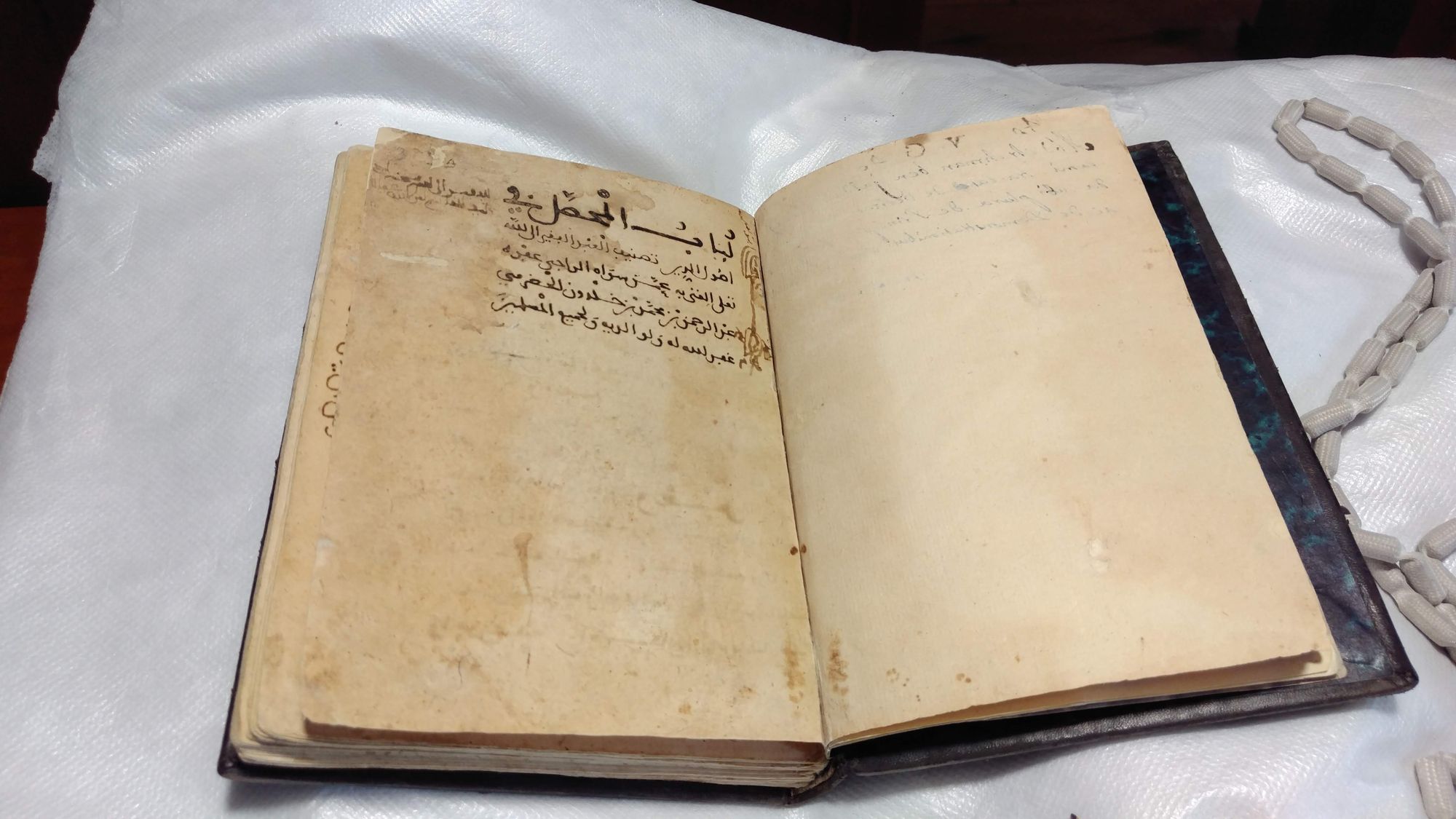

As part of the culmination of his studies, Ibn Khaldun's teacher tasked him with a final assignment concerning Imam al-Razi's al-Muhassal. Ibn Khaldun took on the project to abridge this colossal work of Imam al-Razi and named the work Lubab al-Muhassal. The El-Escorial library in San Lorenzo, Spain houses a copy of an autographed manuscript of Ibn Khaldun's work. Ibn Khaldun himself mentions that this work was issued as an assignment for the culmination and completion of his studies. He mentions that he completed the work in 1351 CE which would make him 19 at the time of writing. At the age of 19, Ibn Khaldun had diligently studied, understood and masterfully summarised the canon of philosophical and theological thought in the Islamic world. This expertise and exposure to rigorous philosophical thinking at such a young age undoubtedly shaped and influenced the future intellectual and scholar Ibn Khaldun was to become.

Conclusion

Youth is the spring of life. It can either be a time of hedonistic enjoyment and self-satisfying fulfilment or it can be a time of self-discovery, growing enlightenment and increasing perfection. These examples from history across the Islamic world highlight a shared culture of contribution, service and a concern for the continuity of tradition that was embedded even within young minds. In all of these anecdotes, a young mind put forward a contribution with sincere effort to serve and benefit others. In doing so, these contributions have outlasted generations and centuries later their legacy is still alive. They weaved forward the fabric of scholarship and thought that enshrouds time, space and fleeting concerns. This note from history should serve as a reminder for us to think of how we can take advantage of our youth before our old age. The past can serve to motivate our present so that we can be mindful of how we continue to weave forward the future.